Comment:

COMMENTS ON MODERATOR’S DEBATING POINTS

By Sergio Duarte*

Q. What is the best way forward, legally and politically, for filling the gap? What are the relative advantages and disadvantages of pursuing a framework convention, compared to a nuclear ban treaty, or a mix of separately negotiated measures?

Q. How important is it for the nuclear weapon states, both the NPT-recognized ones and the other four, to be involved in negotiations right from the start?

Lasting solutions must take into account the legitimate interests of all parties involved. There is no better way to achieve results than making use of the forums offered by international universal organizations such as the United Nations and agencies within its family. Civil society has an important role to play by providing inputs in the form of studies, suggestions and advocacy.

Several universal or near universal treaties starting from the UN Charter in 1945 define the objective clearly: the elimination of all weapons of mass destruction. There is no disagreement on that. The international community has managed to achieve significant, albeit painstaking progress over the past few decades. Important multilateral treaties to prevent proliferation of nuclear weapons were concluded. Two categories of weapons of mass destruction have been (or are being) eliminated: chemical and bacteriological. The international community must now take action to eliminate the last remaining category: nuclear weapons, which have the most destructive and indiscriminate effects on human beings and on the environment.

The proposals for nuclear disarmament presented in the past few years in international forums are not mutually exclusive.

In 2008 Secretary-general Ban Ki-Moon proposed a 5-point plan that included a nuclear weapons convention or “a framework of mutually reinforcing instruments”. This proposal received wide support form a very large and significant majority of United Nations Member States. The Secretary-general did not suggest what specific shape a convention, or a framework, should take. This should be the matter of negotiations. One possible outcome could envisage an immediate and outright prohibition of development, manufacture, stockpiling and use of nuclear weapons to be applicable to all parties. If States that currently possess such weapons accede to such a pact, this would entail a process of elimination of arsenals under an international verification system that would be much more complex than the process of elimination of chemical arsenals under the Chemical Weapons Convention. It would be difficult, but not impossible. Another path would be to start by opening for signature a convention prohibiting the use of nuclear weapons, as some civil society groups advocate. Even if the current nuclear weapon States do not accede immediately to either one of those Conventions, proponents believe its existence – with a significant number of adherents – would create a strong moral standard based on positive international law. Over time, they contend, nuclear weapon States would be compelled to adhere to it under pressure from world public opinion. Irreversible, legally binding agreements to eliminate such weapons under a specific time frame could then follow. Finally, a “framework of mutually reinforcing instruments” could bring existing and future treaties, such as the NPT, the CTBT and other legal texts on nuclear weapons under a chapeau, or general clause that would set forth a clear, legally binding, irreversible commitment to achieve the elimination of nuclear weapons within a specific timeline. These would be the guiding principles for subsequent negotiations of further specific measures.

Skeptics, as well as those interested in keeping the current status quo, may dismiss these ideas as far-fetched or utopian, as it indeed has been the case. However, it is undeniable that seventy years after the UN Charter and forty-five years after the NPT, scant progress on real nuclear disarmament has been achieved. To date, no nuclear weapon has ever been dismantled as a result of a multilateral agreement and the danger of nuclear war, by design or accident, still persists. Reductions agreed between to two largest possessors do not point the way to disarmament, but rather to the perpetuation of a nuclear confrontation at lower levels of armament. States that possess nuclear weapons continue to take measures to maintain and improve their arsenals under the pretext that they are indispensable for their security and that of their allies. Bilateral agreements for reductions of arsenals should be organically linked to a concrete, commitment to achieve their elimination within an agreed timeframe.

Many observers see no inclination on the part of nuclear armed States to take decisive action on nuclear disarmament. Some interpret the often-repeated mantra that atomic arsenals are to be kept “as long as nuclear weapons exist” as a justification for perpetual possession. Perception of a lack of willingness to achieve progress in disarmament provides a strong incentive for further proliferation. Permanent nuclear rivalry, the persistence of a technological arms race under the guise of “modernization” of arsenals and the prospect of further proliferation by additional States – not to mention nuclear terrorism and blackmail – jeopardize the security of all nations, of all individual human beings and of the environment in which we live and on which we all depend.

Q. What is the best forum for negotiating legal instruments for the elimination of nuclear weapons? The traditional forum, the Conference of Disarmament in Geneva, while historically important, has been deadlocked for the past 12 years. Other possibilities include UN forums and structures, including the General Assembly, or Special Sessions of the General Assembly.

In 1978 the First Special Session of the United Nations on Disarmament agreed on a Final Document that set forth a balanced and sensible approach to all questions related to disarmament. It also established multilateral organs to deal with different aspects of the problem. The Disarmament Commission and the First Committee of the General Assembly were tasked with deliberating and formulating recommendations on issues brought before them; the Conference on Disarmament received a mandate to negotiate specific measures; and an Advisory Board was set up to make suggestions to the UN Secretary-general. Over the years, this structure achieved some important multilateral understandings and instruments in the field of disarmament, notably the CWC and the CTBT and set the stage for further progress. To-day, thirty-seven years later, however, the panorama of international relations has changed considerably. It seems now necessary to discuss and agree on fresh ideas and methods that may facilitate progress toward multilateral agreement on further measures aimed at halting the technological nuclear arms race and to reduce and eliminate nuclear weapons, as well as on current problems that affect the security of all nations. Unfortunately, nuclear weapon States and some of their allies have consistently opposed proposals for a new Special Session of the General Assembly on Disarmament.

The longstanding deadlock in the existing negotiating forum – the Conference on Disarmament – should not be blamed on its structure and procedures but mainly reflect the lack of will on the part of nuclear armed States to enter into multilateral negotiations on real measures of nuclear disarmament, which they consider “premature”. Since the inception of the Conference nuclear disarmament has been at the top of its agenda; nevertheless, those States and their allies have systematically prevented any progress in that direction. In order to block consensus on longstanding proposals to negotiate nuclear disarmament agreements or legally binding security assurances to non-nuclear weapon States they invoke of the same rules of procedure – of which, incidentally, they were the main authors – that they now claim to be abused by others.

Disarmament and non-proliferation are two sides of the same coin; they complement each other and can only be effective and lasting if pursued in tandem. However, all instruments that the international community has been able to negotiate and adopt in the nuclear realm so far deal with the prevention of proliferation. None deal with nuclear disarmament proper. To prevent additional States to acquire nuclear means of destruction is of course important and necessary, and the existing international legal framework has been so far successful in containing proliferation. Even so, some States continue to advocate further restrictions on peaceful activities of non-nuclear States and resist proposals for disarmament. For instance, the idea of a ban on the production of fissile material for weapons purposes is actively promoted at the CD. Proposals in that direction were made back in the 1950’s and 1960’s, when only a few advanced industrialized countries could produce such materials in significant quantities. At that time, the prohibition made sense as a measure intended to prevent a nuclear arms race involving a larger number of States. In the present times, however, many consider that such a ban would be redundant, since non-nuclear weapon States are already prohibited under the NPT to produce fissionable material for weapons purposes and their domestic facilities are subject to IAEA safeguards, additional verification measures or equivalent instruments. According to this view, a ban on production would also be innocuous, since under the current proposals, the huge stocks accumulated by the nuclear weapon States would remain untouched. It is indeed hard to see what practical objective such a measure would achieve, except perhaps impose new and stricter constraints on peaceful nuclear activities in developing countries. It would simply reinforce existing non-proliferation restrictions and could hardly be called a “disarmament” measure. Rather, it would leave nuclear-weapon States free to use their stocks of fissile material to improve and expand their arsenals as they see fit.

Q. How best might we continue to galvanize the great majority of countries behind a common approach? What mobilizing and engaging strategies are needed at civil society, governmental and intergovernmental levels?

Q. Can regional organizations and groupings, for example, existing regional NWFZ members and regional civil society networks, play significant advocacy roles in mobilizing support for global measures?

Unfortunately, priorities are not perceived in the same way by different governments. As UN Secretary-general Ban Ki-Moon remarked in 2011, “the world is over-armed and peace is under-funded”. Examples from the past show that it is possible to bring together the will of governments in order to achieve significant measures in the field of disarmament. Latin American States successfully negotiated and adopted instruments such as the Treaty of Tlatelolco, which established the first nuclear weapon free zone and was emulated since in other parts of the world. The agreement among Brazil, Argentina, OPANAL and the IAEA that created the Argentine-Brazilian Agency for Accounting and Control in the 1990’s demonstrated that it is possible for countries to unite for the achievement of common objectives above narrow sectorial interests. In the early 1980’s citizens’ concern for the presence of nuclear weapons in Europe created a powerful push for the negotiation and adoption of the INF Treaty. Every year the United Nations receive millions of signatures on petitions for nuclear disarmament. Many civil society organizations and groups actively advocate nuclear disarmament and seek to educate public opinion and influence their governments. The results of the vote on disarmament issues at successive Sessions of the UN General Assembly show a remarkable and consistent degree of agreement on the general directions to be followed. In 2010 for the first time a Review Conference of the Parties to the NPT recognized the catastrophic consequences of any nuclear detonation. In the past few years, an impressive majority of governments, experts and non-governmental organizations attended three international conferences on this question. Under pressure from public opinion, some nuclear weapon States have shown a degree of willingness to work constructively. This is a promising road that must be pursued and developed. The forthcoming Review Conference of the Parties to the NPT in April/May and the General Assembly of the United Nations are the best forums for progress in this direction. Independent debate on and study of the effects of nuclear explosions should also be encouraged.

Civil society organizations have been a valuable tool to promote advocacy and raise the awareness of populations and governments to the dangers of the existence on nuclear weapons and of the reliance on military doctrines predicated on their use. They can provide encouragement and build momentum to bring about the necessary political will. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, for instance, recently moved its “doomsday clock” forward to three minutes before midnight. Dedicated individuals regularly contribute studies and proposals on nuclear disarmament as well as well-documented analyses of the consequences of the use of atomic weapons and conduct public opinion campaigns. These organizations seek to represent the conscience of the overwhelming majority of populations. Their voice should be heard and their message heeded. It is important to understand, however, that just as governments cannot perform the same function as civil society organizations, the latter cannot and should not take the place of representatives of governments at international bodies composed of States. For good reason civil society organizations are “non-governmental”. They should remain so and develop independent ways to cooperate with governments in order to facilitate the achievement of common objectives.

* Ambassador (ret.), former United Nations High Representative for Disarmament Affairs.

Opening Comments From Chairs

On January 19 2015, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists reset the Doomsday Clock to 3 minutes to midnight – a disturbing reminder of how close we are coming to the brink of human and planetary catastrophe.

The trigger for resetting the clock is the continuing failure of world leaders to deal with the dual threats to human existence posed by climate change, and by “global nuclear weapons modernizations and outsized nuclear weapons arsenals” in a context where “the disarmament process has ground to a halt” (BAS, 19/1/15).

In Geneva, efforts by the Conference on Disarmament to even start negotiations on modest arms control and non-proliferation measures have been frustrated for over 12 years as a result of the abuse of the consensus rule.

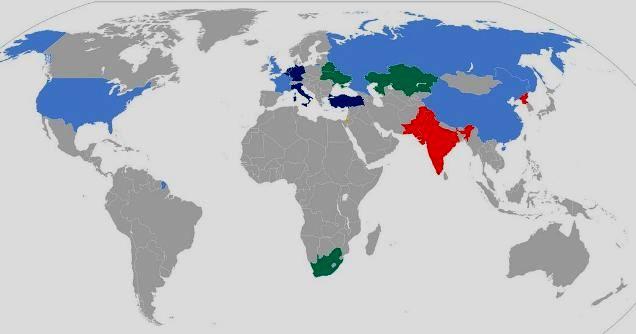

In the Non-Proliferation Treaty context, the five NPT-recognised nuclear powers have failed to make adequate progress on substantive nuclear disarmament negotiations as required under Article VI; and nuclear weapon states outside the NPT framework, including Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea, are continuing to reject any constraints on their nuclear arsenals, and are themselves beginning to provoke further nuclear acquisition and threats within their respective regions, especially in the Middle East.

Despite pressure to convene a conference to discuss a Middle East Weapon of Mass Destruction Free Zone (as agreed at the last 2010 NPT Review Conference), the US and Israel have sought to delay the conference; and the NPT itself may unravel as member states draw their own conclusions about being constrained by the NPT while other regional states are allowed to acquire and threaten to use nuclear weapons.

In the Ukraine conflict, two nuclear armed parties, Russia and NATO, are potentially becoming involved in a proxy war, with increased tension and confrontation along NATO/Russian borders, a crisis that, if not resolved quickly, may yet lead to inadvertent launches of nuclear weapons, as, most frighteningly, nearly occurred during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Despite this ominous context, the Humanitarian Initiative on Nuclear Weapons, launched by Norway at the Oslo Conference in March 2013, was taken further at the Narayat Conference in Mexico in February 2014, and further still at the Vienna Conference in December 2014. This initiative offers some hope of finally moving towards a greater commitment on the part of the world community to deal with the nuclear threat.

Attended by 158 UN member states, including two NPT-recognised nuclear weapon states (the US and UK), the Vienna Conference made substantive progress on highlighting the humanitarian transboundary catastrophic consequences of even a limited nuclear war, and the greatly increasing risks of nuclear conflict as a result of proliferation, accident, miscalculation, non-state actor acquisition, and cyber-attacks.

The conference went further still in focusing on the legal gap in the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons compared to chemical and biological weapons, despite the fact that nuclear weapons pose a far greater risk of destroying the very conditions for continued human existence. An increasing number of states, 44 UN member states, are now calling for immediate negotiations on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.

Austria, for its part, has issued the Austrian Pledge with the aim of having all NPT parties at the (27 April-22 May) 2015 NPT Review Conference in New York commit to “the urgent and full implementation of existing obligations under Article VI, and, to this end, to identify and pursue effective measures to fill the legal gap for the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons”.

Civil society groups active on the issue, particularly the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), called at the Vienna Conference for immediate action to fill this legal gap, including, potentially through a legally binding instrument or treaty that bans nuclear weapons similar to the conventions that outlaw chemical and biological weapons. At the Vienna Conference, immediate negotiation of a ban treaty continued to be opposed by nuclear weapons states (and some of their allies, who cited the need for “security” in the form of “extended deterrence” arrangements). New Zealand pointedly asked what these countries meant by “security” but failed to receive answers. Clearly, with the evidence now available on the transboundary human and economic devastation and decade-long nuclear winter following even a limited (100 bomb) nuclear exchange, national notions of security no longer apply.

Despite the impetus generated by the Humanitarian Initiative, there are issues both within governments and within civil society antinuclear movements as to the most effective ways to break through the current nuclear disarmament impasse.

One issue is the appropriate legal instrument to be pursued. This might take the form of a framework nuclear weapon convention involving (as currently proposed by the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in a working paper to the 2015 NPT Review Conference) “a phased program for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons within a specific timeframe”.

Alternatively, it might take the form of a nuclear ban treaty that is immediately negotiated amongst like-minded states with or without the initial participation of the nuclear weapon states. The expectation here is that nuclear weapon states will come under pressure to join at a later date.

Yet a third approach, not necessarily incompatible with either of the other two approaches (but potentially diverting attention away from them), is to pursue multiple but partial measures, tackling various aspects of the nuclear threat, such as the Fissile Material Control Treaty under discussion in the CD, the CTBT, de-alerting, reductions in nuclear arsenals, outlawing of particular classes of nuclear weapons, new systems of verification and compliance, and a further expansion of regional and national NWFZs.

As of now there appears no overall consensus on the best way to fill the “legal gap”.

This suggests an important question on which to focus our conversation:

What is the best way forward, legally and politically, for filling the gap? What are he relative advantages and disadvantages of pursuing a framework convention, compared to a nuclear ban treaty, or a mix of separately negotiated measures ?

A related question worth exploring is:

How important is it for the nuclear weapon states, both the NPT-recognized ones and the other four, to be involved in negotiations right from the start?

Yet another question might be:

What is the best forum for negotiating legal instruments for the elimination of nuclear weapons? The traditional forum, the Conference of Disarmament in Geneva, while historically important, has been deadlocked for the past 12 years. Other possibilities include UN forums and structures, including the General Assembly, or Special Sessions of the General Assembly.

Given the increased impetus generated by the Humanitarian Initiative conferences one further question is worth posing:

How best might we continue to galvanize the the great majority of countries behind a common approach? What mobilizing and engaging strategies are needed at civil society, governmental and intergovernmental levels?

In all of this the regional dimension should not be overlooked:

Can regional organizations and groupings, for example, existing regional NWFZ members and regional civil society networks, play significant advocacy roles in mobilizing support for global measures?